História

Pravek

Prvé zachované dôkazy o osídlení Slovenska pochádzajú z konca paleolitu približne spred 250 tisíc rokov. Klimaticky je to veľmi dlhé obdobie striedania ľadových dôb s medziľadovými dobami. Z tohto obdobia pochádza nález lebky neandertálca v Gánovciach a nález sošky Venuše v Moravanoch. Približne v rokoch 5000 – 4000 p. n. l. sa objavujú prví roľníci (nálezy kamenných sekier, klinov, nádob v jaskyni Domica).

V dobe bronzovej sa na Slovensku vyskytovalo veľké množstvo rôznych archeologických kultúr. Ich pozostatkami boli aj nálezy početných bronzových kosákov, voza s kolesami z ohýbaných rámov a stopy po drevených stavbách budovaných bez použitia klincov.

Železná doba a technológie s ňou spojené prišli na Slovensko pravdepodobne z oblasti Anatólie alebo Itálie. Na Slovensku sa začala rozvíjať ťažba železa, olova, zlata a soli. Po prvýkrát sa tu objavil hrnčiarsky kruh.

Príchod Keltov

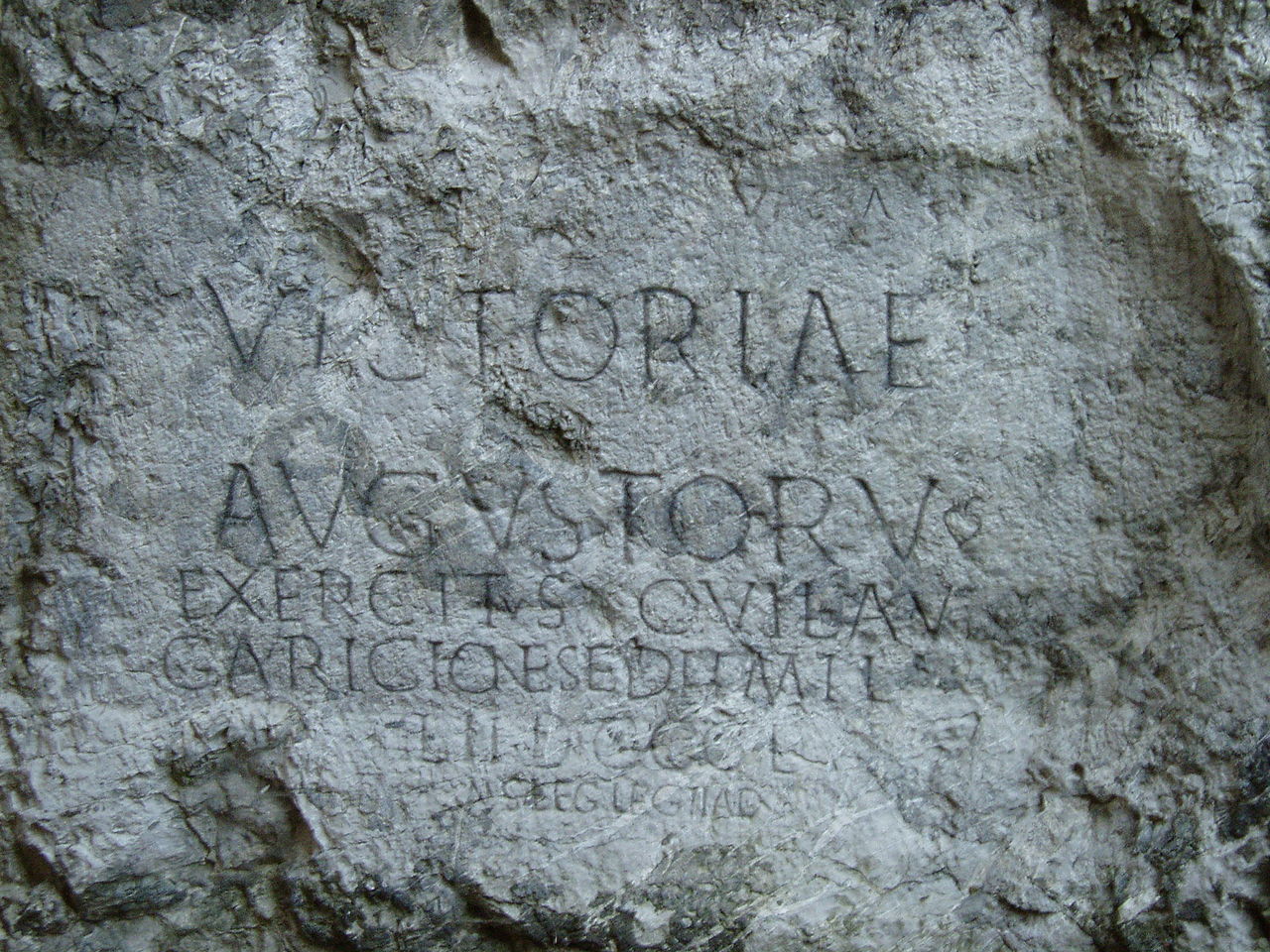

Od konca 4. storočia p. n. l. prichádza na Slovensko vo viacerých vlnách prvé menovite známe etnikum - Kelti. O ich prítomnosti sa nám zachovali písomné zmienky v rímskych prameňoch.

Kelti vytvorili niekoľko opevnených osád - oppíd. Niektoré z nich, napríklad Bratislavské oppidum, sú odvtedy dokázateľne nepretržite osídlené. Väčšina z nich však žila v neveľkých osadách, domy si stavali z dreva, domy sa zamykali železnými zámkami. Kelti boli zruční remeselníci - kováči, hrnčiari, minciari, poľnohospodári aj obchodníci. Udržovali úzke kontakty s gréckou a rímskou civilizáciou, ktoré mali na ich kultúru veľký vplyv.

V 1. storočí p. n. l. prichádzajú na územie dnešného Slovenska Dákovia a dochádza k miešaniu keltského a dáckeho obyvateľstva a kultúry. Roku 10 p. n. l. však Dákov porazili Rimania a posunuli hranice Rímskej ríše na stredný Dunaj. Dácke obyvateľstvo mizne zo Slovenska niekedy v 1. storočí n. l. Likvidáciu väčšiny Keltov zavŕšili výboje Germánov zo severozápadu. Kelti sa udržali na severe Slovenska až do 2. storočia n. l.

Koncom 4. storočia sa už Rímska ríša nachádzala v hlbokom úpadku. Začalo sa sťahovanie národov, ktoré prispelo k rozpadu Rímskej ríše. Veľká časť pôvodného obyvateľstva z krajiny buď ušla alebo podľahla v boji novým národom. Územím Slovenska vtedy prechádzali mnohé kmene, napríklad Vizigóti, Ostrogóti či Longobardi a Gepidi, v dôsledku útoku kočovných Hunov. Tí si vytvorili centrum v blízkom susedstve Slovenska - medzi Tisou a Dunajom.

Príchod Slovanov

Jedným z kmeňov, ktorý postupoval vo viacerých vlnách v tomto období do krajiny, boli aj Slovania. Prvé vlny prišli na naše územie v priebehu 5. a 6. storočia. Noví prisťahovalci často zostali žiť medzi pôvodným obyvateľstvom. Slovania v tej dobe kolonizovali asi len 10% územia, zvyšok bol ešte stále divokou nedotknutou krajinou. Poznali jačmeň, proso, pšenicu, mak, ľan. Živili sa poľnohospodárstvom a chovom dobytka. Boli aj schopní remeselníci - najmä šperkári a hrnčiari. Slovania sa na západe dostali do styku s Franskou ríšou. Keďže Slovania sa sprvu nezúčastnili žiadnych veľkých bojov, zachovalo sa z tohto obdobia len veľmi málo písomných zmienok.

V polovici 6. storočia vtrhli do Podunajskej nížiny kmene Avarov. Slovania pod ich vplyvom prestali svojich mŕtvych spaľovať a začali s kostrovým pochovávaním.

Samova ríša

V 6. storočí sa Slovania dostali do područia kočovných kmeňov Avarov, čo vyvolalo niekoľko povstaní. Jedného z nich sa zúčastnil aj istý franský kupec Samo, ktorého si nakoniec Slovania pre jeho statočnosť a vojenské kvality zvolili za kráľa kmeňového zväzku - Samovej ríše (623-658). Po Samovej smrti roku 658 sa kmeňový zväz Slovanov opäť rozpadol.

Veľká Morava

Od 8. storočia sa začínajú slovanské kmene opäť zjednocovať. V prvej polovici 9. storočia vznikajú dva nové útvary, Moravské kniežatstvo (na čele Mojmír I.) a Nitrianske kniežatstvo (na čele Pribina). Roku 833 vyhnal Mojmír I. Pribinu z Nitrianskeho kniežatstva a obe kniežatstvá spojil, čím vznikla Veľká Morava. Vyhnaný Pribina sa usadzuje pri Blatenskom jazere, kde stavia hradisko Blatnohrad.

Rast vplyvu Veľkomoravskej ríše vyvolával odpor Východofranskej ríše. V snahe zbaviť sa východofranského vplyvu panovník Rastislav sa v roku 861 obrátil na pápeža Mikuláša I. s prosbou o biskupa a kňazov, aby vyučili duchovenstvo, no neuspel. S rovnakou prosbou sa obrátil na byzantského cisára Michala III. a ten roku 863 posiela na Moravu učiteľov viery na čele so sv. Konštantínom a Metodom.

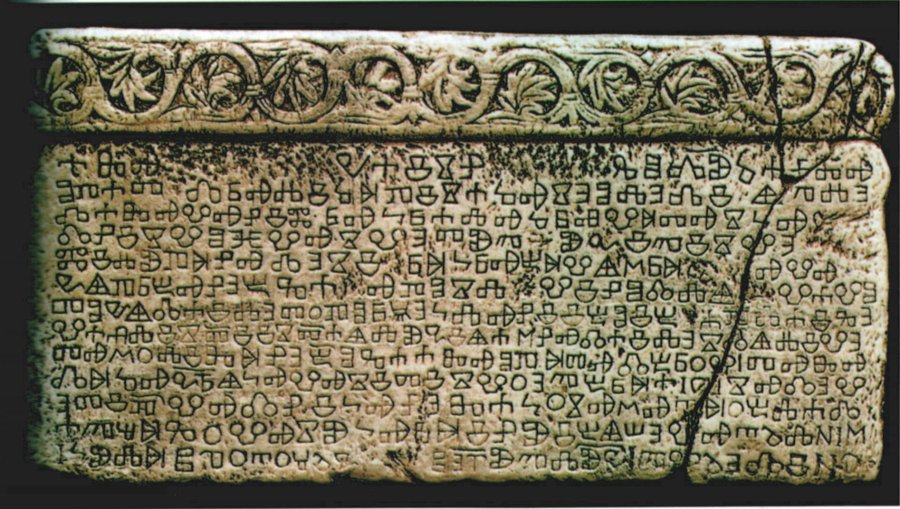

Konštantín (pred smrťou prijal aj rehoľné meno Cyril) a Metod ihneď po príchode na Moravu založili prvé slovanské učilište (Veľkomoravské učilište, kde vyučovali slovanské duchovenstvo), zostavili slovanské písmo - hlaholiku, zaviedli staroslovienčinu do náboženských obradov a priniesli preklady liturgických a biblických textov, ktoré už predtým pripravili. Ich misia na Veľkej Morave predstavuje dôležitú etapu v histórii Slovanov a Slovákov.

O zániku Veľkej Moravy sa nám nezachovali presné informácie. Po útoku kočovných kmeňov Maďarov pod velením Arpáda roku 906 alebo 907 Veľká Morava pravdepodobne stratila svoj vplyv, postupne sa rozpadla a územie Slovenska sa začalo začleňovať do novovznikajúceho Uhorska.

Slovensko v Uhorsku

Roku 1000 sa Štefan I., ktorý zavŕšil proces formovania Uhorska, stáva prvým uhorským kráľom. Územie Slovenska sa stalo súčasťou Uhorského kráľovstva na takmer tisíc rokov. V 16. storočí sa objavuje turecké nebezpečenstvo, od roku 1521 Osmanská ríša tiahne na Uhorsko. Kráľ Ľudovít II. Jagelovský podcenil nebezpečenstvo a 29. augusta 1526 v bitke pri Moháči bolo uhorské vojsko porazené a sám kráľ padol, utopil sa vo vlnách Dunaja. Porážka v bitke pri Moháči rozhodla o tom, že v Uhorsku ďalších 175 rokov vládli Turci. Turci boli porazení až roku 1683 pri Viedni. Začalo sa postupné vytláčanie Turkov z Uhorska, definitívne zavŕšené roku 1685.

Roku 1740 nastupuje na trón Mária Terézia. ktorá je známa najmä svojimi reformami. Zreformovala armádu a zakladala manufaktúry, niekoľko aj na Slovensku (Šaštín, Halič, Holíč). V poľnohospodárstve podporovala pestovanie nových plodín. Zreformovala aj súdnictvo, zmiernila niektoré tresty a prijala sa zásada, že všetci občania sú si pred súdom formálne rovní. Reformou školstva (Ratio educationis) zaviedla povinnú školskú dochádzku a položila základy vyspelejšieho školstva.

Jej syn Jozef II. pokračoval v reformácii Uhorska. Roku 1781 vydáva tzv. „tolerančný patent“, ktorým dal protestantom a iným nekatolíckym konfesiám určité náboženské slobody. Roku 1785 zrušil stoličnú samosprávu a nahradil ju desiatimi štátnymi dištriktmi, presunul mnohé centrálne uhorské úrady zo Slovenska do Budína a zrušil nevoľníctvo v Uhorsku (roku 1781 v Čechách).

Slovenské národné obrodenie

Proces formovania slovenského národa mal mimoriadne ťažký priebeh (útlak zo strany maďarskej šľachty, maďarský nacionalizmus a represie na území Slovenska). Obhajcom slovenských práv sa stáva inteligencia, hlavne kňazi. Medzi hlavné ciele patrilo najmä uzákonenie spisovnej slovenčiny.

Ako prvý sa o kodifikáciu slovenčiny pokúsil katolícky farár Jozef Ignác Bajza, ktorý napísal prvý román v slovenčine René mládenca príhody a skúsenosti vydaný v roku 1783. Jeho jazyková forma však nebola ustálená, a tak sa jeho návrh neujal.

Inteligencia bola v tom čase rozdelená na katolíkov a evanjelikov. Katolíci požadovali pre Slovákov vlastný jazyk, evanjelici presadzovali biblickú češtinu, jednotu Čechov a Slovákov a odmietali kodifikáciu spisovnej slovenčiny.

Katolícky kňaz Anton Bernolák kodifikoval roku 1787 spisovnú slovenčinu (nazývanú bernolákovčina) na základe západoslovenského nárečia.

Druhým úspešným kodifikátorom bol Ľudovít Štúr. Začiatkom roku 1843 oboznámil Štúr svojich blízkych priateľov s myšlienkou spojiť katolícky aj evanjelický prúd Slovákov na báze jednotného spisovného jazyka. Za základ vybral stredoslovenské nárečie najmä pre jeho rozšírenosť, pôvodnosť a zrozumiteľnosť. 11. júla 1843 sa Ľ. Štúr, J. M. Hurban a M. M. Hodža stretli na Hurbanovej fare v Hlbokom, kde sa dohodli na postupe pri zavedení slovenčiny do praxe.

Slovensko po rozpade Uhorska

28. októbra 1918 sa Slovensko stalo súčasťou Česko-Slovenska. Spomedzi slovenských osobností sa o založenie republiky zaslúžil najmä M. R. Štefánik, ktorý ako diplomat v službách Francúzska pomohol T. G. Masarykovi a E. Benešovi nadviazať kontakty s predstaviteľmi Dohodových mocností. Aktívne organizoval vznik čs. légií, čo viedlo k vytvoreniu disciplinovanej a akcieschopnej armády, nazvanej Československé légie. Prvým prezidentom krajiny sa stal 14. novembra 1918 Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. Slovensko bolo súčasťou Česko-Slovenska do roku 1939, kedy vznikla prvá Slovenská republika.

Po 2. svetovej vojne bolo Česko-Slovensko obnovené a dostalo sa do sféry vplyvu ZSSR. 11. júla 1960 bola schválená nová ústava, ktorá deklarovala to, že v Československu zvíťazil socializmus. Názov Československá republika (ČSR) sa zmenil na Československá socialistická republika (ČSSR) a bol oficiálne vyhlásený socialistický štát. Zmena režimu, ako aj obrat v zahraničnej politike, nastali až po novembri 1989, kedy prebehla tzv. Nežná revolúcia. Československo sa stalo opäť demokratickým štátom, orientovaným najmä na Západ. Na jar roku 1990 bola prijatý ústavný zákon obsahujúci aj zmenu názvu celého štátu na Českú a Slovenskú federatívnu republiku (ČSFR). V júni 1990 sa v ČSFR konali prvé slobodné voľby. Krátko po schválení dokumentu Deklarácia o zvrchovanosti Slovenskej republiky Slovenskou národnou radou (17. júla 1992) sa víťazi českých a slovenských volieb dohodli v Bratislave na rozdelení štátu.

1. septembra 1992 bola prijatá a 3. septembra 1992 podpísaná Ústava SR. 1. januára 1993 nasledoval pokojný zánik ČSFR, rozdelenie krajiny na dnešné Slovensko a Česko. Po 75 rokoch existencie spoločného štátu Čechov a Slovákov tak vznikla Slovenská republika, ktorej prvým prezidentom sa stal Michal Kováč.

intro.slovakia.general.source http://sk.wikipedia.org